Understanding Modern Counterterrorism: Strategies, Intelligence, and the Evolving Threat Landscape

I. Introduction: The Enduring Challenge of Terrorism

Terrorism remains a persistent and complex threat to national and international security. Its impact extends far beyond the immediate casualties, affecting political stability, economic prosperity, social cohesion, and individual psychology. Understanding the nature of this threat and the strategies employed to counter it is crucial for navigating the contemporary security landscape. This requires grappling with the fundamental challenge of defining terrorism itself, recognizing its multifaceted impact, and appreciating the intricate web of intelligence and strategic components necessary for an effective response.

A. Defining the Elusive Concept: Terrorism

Defining terrorism is notoriously difficult, with interpretations varying significantly between legal frameworks, academic discourse, and international bodies. Governmental and legal definitions are primarily operational necessities, designed to establish jurisdiction, criminalize specific acts, and empower authorities to act against perceived threats. A prominent example is the UK’s Terrorism Act 2000, which defines terrorism as the use or threat of specific actions – including serious violence against persons, serious damage to property, endangering life (other than the perpetrator’s), creating serious public health or safety risks, or seriously interfering with or disrupting electronic systems – where such action is designed to influence a government or international governmental organisation or intimidate the public (or a section thereof) for the purpose of advancing a political, religious, racial, or ideological cause. Notably, the Act specifies that the use or threat of firearms or explosives constitutes terrorism regardless of whether the design is to influence or intimidate. This definition also applies to actions outside the UK and forms the basis for proscribing organisations deemed to be “concerned in terrorism” and prosecuting related offences like preparing for terrorism, collecting information useful for terrorism, or disseminating terrorist publications. Similarly, the United States distinguishes between international terrorism (inspired by or associated with foreign groups/nations) and domestic terrorism (stemming from domestic influences like political, religious, or racial motives).

Academic definitions, conversely, often delve deeper into the nature and purpose of the violence, seeking a broader conceptual understanding. Common themes emerge: the deliberate use or threat of violence , calculated to create fear, terror, and alarm in a wider audience than the immediate victims. This psychological impact is central, aiming to coerce or intimidate populations or governments into changing behaviour or policy. The targeting of non-combatants or civilians is another frequently highlighted element , distinguishing terrorist violence from conventional warfare. This reflects the classic “terrorist triangle” where A attacks B to coerce C. The motive is typically political or ideological.

Despite these common threads, achieving a universally agreed-upon legal definition remains elusive. The term “terrorism” is inherently political and often contested, particularly regarding the legitimacy of violence used by non-state actors versus states, or in struggles for self-determination. The United Nations, for instance, has struggled for decades to adopt a comprehensive convention against international terrorism, largely due to these political disagreements. While UN Security Council resolutions like 1566 offer influential working definitions – criminal acts intended to cause death/injury or hostage-taking to provoke terror, intimidate a population, or compel action – they lack the force of a universally binding treaty definition.

The way terrorism is defined is not merely an academic exercise; it fundamentally shapes the response. Governmental definitions, like the UK’s , are pragmatic tools enabling law enforcement and security services to investigate, prosecute, and disrupt activities deemed terrorist. They must be precise enough for legal application yet adaptable to evolving threats, such as the inclusion of disrupting electronic systems. Academic definitions probe the underlying dynamics of the phenomenon. The persistent international disagreement, exemplified by the UN’s challenges , reflects deep-seated political conflicts over the legitimacy of violence. This definitional ambiguity carries risks: overly broad or vague definitions can be misused by states to suppress dissent or target specific groups, undermining human rights and the rule of law under the guise of counterterrorism.

B. The Multifaceted Impact on National Security

The consequences of terrorism ripple outwards, impacting nations far beyond the immediate violence. The direct human cost is stark, violating fundamental rights to life, liberty, and physical integrity. Attacks cause death, injury, and displacement, leaving lasting trauma on victims, families, and communities.

Politically, terrorism seeks to destabilize. It aims to undermine governments, erode public trust in institutions, influence policy through intimidation, and disrupt civil society. In the modern era, hostile actors may leverage or align with terrorist acts, using disinformation campaigns to further sow discord, amplify division, and undermine democratic processes, compounding the political impact.

Economically, the disruption can be severe. Attacks damage critical national infrastructure (CNI) – energy grids, transportation networks, communication systems, financial institutions, and increasingly, cyber infrastructure – vital for societal functioning. Recent cyber incidents, whether criminal ransomware attacks like the one impacting the UK’s NHS via Synnovis or state-sponsored intrusions like Volt Typhoon targeting US CNI , illustrate the potential for widespread service disruption with significant economic consequences. Terrorism also disrupts trade and travel, necessitates costly security measures, and can harm national economic competitiveness.

Socially, terrorism aims to fracture societies. It can deliberately target specific ethnic or religious communities, exacerbating tensions and fostering inter-group hostility. Even indiscriminate attacks create climates of fear, suspicion, and anxiety, potentially leading to social polarization and the erosion of community cohesion.

Psychologically, the goal is often terror itself – creating fear and alarm disproportionate to the physical damage inflicted. This impacts public morale, alters perceptions of safety, and can influence public behaviour and political discourse.

Ultimately, terrorism poses direct threats to the safety of citizens, the integrity of government and military facilities, the functioning of critical infrastructure (physical and cyber), and the security of symbolic locations chosen for their resonance.

It becomes clear that terrorism functions as a threat multiplier. An attack is not an isolated event but a catalyst for cascading consequences across multiple domains. Damage to critical infrastructure causes immediate service loss but also shakes public confidence , incurs economic costs , and can be politically exploited. The fear generated can polarize society and create pressure for security responses that may themselves infringe on rights and freedoms. Adversaries, whether state or non-state, understand this dynamic and may employ terrorism or related tactics like disinformation precisely to achieve these broader destabilizing effects. Consequently, a robust counterterrorism strategy must address not only the immediate violence but also these wider impacts, focusing on societal resilience alongside disruption and prevention.

II. Setting the Course: National Counterterrorism Objectives

Given the severe and multifaceted nature of the terrorist threat, nations develop comprehensive strategies aimed at mitigating the risk. While specific approaches vary, core objectives are broadly shared across democratic states.

A. Core Goals

The primary objectives of national counterterrorism efforts typically include:

- Preventing Attacks: This is the foremost priority – stopping terrorist acts before they occur. A crucial component is preventing individuals from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism in the first place, often involving efforts to counter radicalization.

- Disrupting Networks and Operations: Weakening terrorist groups by targeting their leadership, finances, communications, recruitment, travel, and logistical capabilities.

- Responding to Incidents: Effectively managing the aftermath of an attack to minimize its impact, save lives, and restore normalcy.

- Bringing Perpetrators to Justice: Holding terrorists accountable through investigation, arrest, prosecution, and incarceration, utilizing law enforcement and the judicial system.

- Protecting Critical Infrastructure and Citizens: Hardening potential targets, including CNI (energy, transport, water, communications, finance, health, etc.), government facilities, public spaces, and the populace, against both physical and cyber attacks.

- Countering Extremist Ideologies: Challenging and undermining the narratives, propaganda, and belief systems that underpin terrorist violence.

- Addressing Root Causes: Working to diminish the underlying conditions – such as political grievances, social exclusion, economic deprivation, and lack of rule of law – that terrorist groups exploit to gain support and recruits.

B. Illustrative Framework: The UK’s CONTEST Strategy

The United Kingdom’s counter-terrorism strategy, known as CONTEST, provides a clear example of how these objectives are structured and pursued. First established in 2003 and updated periodically (most recently in 2023), CONTEST aims “to reduce the risk from terrorism to the UK, its citizens and interests overseas so that people can go about their lives freely and with confidence”. It is organized around four pillars, often referred to as the “Four Ps”:

- Prevent: This pillar directly addresses the objective of stopping people from becoming terrorists or supporting terrorism. Following an independent review, its focus includes tackling the ideological causes of terrorism, intervening early to support individuals vulnerable to radicalisation (through multi-agency programmes like Channel), and enabling the rehabilitation of those already involved in terrorism. Prevent operates through a partnership approach involving local authorities, police, education, health, and other sectors, mandated in part by the Prevent Duty under the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015. It is explicitly a voluntary, consent-based safeguarding programme.

- Pursue: The objective here is to stop terrorist attacks from happening. This involves the core operational work of detecting, investigating, and disrupting terrorist threats. Counter Terrorism Policing (CTP) works closely with the security service (MI5) to develop intelligence and gather evidence for prosecution. Detection relies heavily on intelligence gathering and analysis, but also encourages public reporting of suspicious activity through initiatives like Action Counters Terrorism (ACT).

- Protect: This strand aims to strengthen the UK’s protection against attacks, thereby reducing vulnerability. Key areas include enhancing border security, securing the transport system, protecting critical national infrastructure (CNI), and improving security in public places. Legislation such as the proposed Martyn’s Law, aimed at increasing preparedness at public venues, falls under this pillar. Public awareness campaigns also contribute to this objective.

- Prepare: Where an attack cannot be stopped, the Prepare pillar seeks to minimise its impact. This involves ensuring effective coordination of emergency response efforts, facilitating recovery, building resilience in communities and infrastructure, and learning lessons to improve future preparedness.

The effectiveness of a strategy like CONTEST hinges on the seamless integration and interaction between these four pillars. Success in Prevent reduces the pool of potential recruits, lessening the burden on Pursue. Robust Protect measures make potential targets less attractive or harder to attack, potentially deterring plots or forcing terrorists towards methods more easily detected by Pursue. Effective Prepare capabilities limit the strategic success of any attack that does occur, reducing the terrorists’ ability to achieve objectives like mass panic or societal disruption. Intelligence gathered under Pursue directly informs Protect priorities regarding which locations or infrastructure need hardening. Lessons learned from incident response under Prepare feed back into refining Prevent programmes and Protect measures. This interdependence necessitates strong collaboration and information sharing across multiple government departments and agencies – including police, intelligence services (MI5, GCHQ, SIS), local authorities, health and education providers, and increasingly, the private sector – to ensure a truly cohesive national effort. A fragmented or siloed approach risks missing critical opportunities for intervention, disruption, or mitigation.

III. Anatomy of a Modern Threat: ISIS/Daesh Case Study

To understand the challenges faced by counterterrorism efforts, examining a specific terrorist organization is instructive. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), also known as ISIL or Daesh, provides a compelling case study of a modern, adaptive, and impactful terrorist group.

A. Origins and Ideology: The Salafi-Jihadist Vision and the Caliphate

ISIS traces its roots to Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), founded by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi in 2004. It capitalized on the instability following the 2003 Iraq War and later the Syrian Civil War, expanding its influence and capabilities.

The group’s ideology is a potent and extreme blend of Salafi-jihadism, Sunni Islamist fundamentalism, Wahhabism, and Qutbism. Drawing heavily on the revolutionary ideas of Sayyid Qutb and the medieval theology of Ibn Taymiyya , ISIS espouses several core tenets:

- Restoration of the Caliphate: Central to its identity was the declaration of a Caliphate in June 2014, claiming to restore the rightful Islamic leadership of the early Muslim community (umma). ISIS demanded religious, political, and military allegiance from all Muslims worldwide. This state-building project was a key differentiator from Al-Qaeda’s focus on a vanguard movement.

- Strict Interpretation of Sharia: ISIS enforced an extreme and literalist interpretation of Islamic law within the territories it controlled.

- Takfirism (Excommunication): A core element was the practice of takfir – declaring other Muslims, particularly Shia Muslims but also Sunnis who opposed them, as apostates deserving of death. This fueled extreme sectarian violence.

- Apocalyptic Beliefs: ISIS incorporated beliefs about the nearing Day of Judgment and final battles, adding a millenarian dimension to its ideology.

- Rejection of Modernity: The ideology rejects modern nation-states, borders, democracy (seen as man-made law usurping God’s sovereignty), and Western influence.

- Armed Jihad: Violence is viewed as a necessary and obligatory instrument to defend Islam, expand the Caliphate (dar al-Islam), and fight perceived enemies (“near” enemies like regional regimes and “far” enemies like the West).

Motivations for individuals joining ISIS were varied, often combining religious conviction with responses to perceived political or socio-economic grievances, a sense of alienation, the desire for purpose and belonging within the promised utopian Caliphate, or the appeal of its violent ideology.

B. Tactics and Methods: From Bombings to Propaganda

ISIS employed a diverse and brutal range of tactics:

- Military and Insurgent Warfare: When controlling territory, ISIS utilized conventional military tactics alongside insurgent methods. This included large-scale assaults on military and government targets , ambushes , targeted killings , and extensive use of Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), roadside bombs, mines, rockets, and vehicle-borne IEDs (VBIEDs). Suicide bombings were a common and devastating tactic, adapted for urban warfare scenarios. After losing its territorial caliphate, the group reverted more heavily to guerrilla and insurgent tactics.

- Kidnapping and Executions: ISIS frequently used kidnapping, both for ransom to generate funds and for propaganda purposes, often culminating in brutal public executions (including beheadings) of hostages, including soldiers, journalists, aid workers, and civilians deemed enemies.

- Propaganda and Recruitment: ISIS demonstrated exceptional mastery of modern media and propaganda. It produced high-quality online magazines (like Dabiq) , professionally edited videos, and utilized social media platforms extensively to disseminate its message, glorify violence, project an image of strength and statehood (the Caliphate), and recruit fighters globally. A key aim was attracting foreign terrorist fighters (FTFs) and inspiring sympathizers worldwide to conduct lone-actor attacks in their home countries. ISIS propaganda often exploited real or perceived grievances and employed sophisticated emotional and religious appeals.

- Cyber Activities: While specific details on ISIS’s offensive cyber capabilities are limited in the provided materials, terrorist groups in general leverage the internet and cyber means for crucial functions: communication, planning, fundraising, intelligence gathering, recruitment, radicalization, and propaganda dissemination. The potential for terrorists to conduct attacks designed to seriously disrupt electronic systems is recognized as a form of terrorism itself.

C. Targeting Strategy: Who and What ISIS Attacks

ISIS’s targeting strategy reflected its ideology and objectives:

- Military and Security Forces: Primary targets in conflict zones like Iraq, Syria, Nigeria, and Libya included national armies, police, and associated security forces.

- Government Personnel and Infrastructure: ISIS attacked government officials and facilities, including prisons, government buildings, and electoral commissions, aiming to undermine state authority. Critical infrastructure, such as oil facilities in Libya, was also targeted.

- Civilians: Civilians were frequently and brutally targeted. This included indiscriminate attacks in public spaces like markets and religious sites (both mosques and churches) to spread terror. Specific groups were targeted based on ideology: Shia Muslims were considered apostates , minority groups like Yazidis faced genocide , and Christians were persecuted. Civilians perceived as collaborating with opposing forces were also targets.

- Foreigners and International Entities: Foreign aid workers, journalists, tourists, and citizens of coalition countries were specifically targeted through kidnappings, executions, and attacks. UN facilities were also attacked.

- Symbolic Targets: ISIS attacked locations with significant religious or cultural value, including mosques , churches , and ancient cultural heritage sites, aiming to erase history and impose its worldview. Attacks were also directed at symbols of Western influence or presence.

- Rival Groups: ISIS engaged in conflict with other militant groups, notably breaking from Al-Qaeda and fighting against groups like Boko Haram in West Africa.

The group’s actions demonstrate a clear link between its extremist ideology and its operational conduct. The ambition to build and defend a Caliphate drove territorial conquest and attacks on state forces. The doctrine of takfir provided justification for mass violence against specific religious and ethnic groups. Its apocalyptic and anti-Western worldview fuelled extreme brutality and attacks targeting Western interests and citizens. The sophisticated use of propaganda was essential for recruitment and projecting power. Therefore, effectively countering groups like ISIS necessitates not only degrading their military and operational capabilities but also confronting and delegitimizing the potent ideology that motivates their actions and attracts followers. Understanding this ideology provides crucial insights into potential future targets and tactics.

IV. The Eyes and Ears: Intelligence in Counterterrorism

A. The Criticality of Intelligence Gathering and Analysis

Intelligence is the bedrock of any effective counterterrorism strategy. In a complex and evolving threat landscape – characterized by diverse actors (foreign terrorist organizations, domestic extremists, lone offenders) , dispersed networks, online radicalization , and the transnational nature of the threat – timely, accurate, and actionable intelligence is indispensable for understanding threats, preventing attacks, and guiding responses.

National intelligence communities, comprising agencies like MI5, GCHQ, and SIS in the UK , and the CIA, NSA, NGA, FBI, and others in the US , are tasked with this mission. Coordination bodies such as the UK’s Joint Terrorism Analysis Centre (JTAC) and the US National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) play vital roles in integrating intelligence from various sources and ensuring information is shared effectively across the government. The goal is to move beyond simply collecting information to producing finished intelligence that provides insight, context, and predictive assessments to decision-makers.

B. Key Intelligence Disciplines (INTs) Explained

Counterterrorism intelligence relies on multiple collection methods, often referred to by their discipline or “INT”:

- HUMINT (Human Intelligence): This is intelligence gathered from human sources through methods like espionage, running informants, debriefings, interviews, and liaison with foreign partners. Often considered the oldest intelligence discipline , HUMINT provides unique insights into adversary intentions, plans, leadership dynamics, and internal group information that technical means may not capture. Agencies like the UK’s Secret Intelligence Service (SIS or MI6) and the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) are primary collectors of HUMINT overseas.

- SIGINT (Signals Intelligence): This involves the interception and analysis of electronic signals. It encompasses Communications Intelligence (COMINT), focusing on the content and metadata of communications (phone calls, emails, radio messages) , and Electronic Intelligence (ELINT), which deals with non-communicative signals like radar emissions or weapons systems telemetry. SIGINT is crucial for tracking terrorist communications and networks, identifying connections, monitoring movements, and understanding technical capabilities. The UK’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) and the US National Security Agency (NSA) are the lead agencies for SIGINT.

- OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence): This discipline involves the collection, exploitation, and analysis of publicly available information. Sources include traditional media, the internet (websites, forums, blogs), social media platforms, public government data, academic publications, and commercial databases. In the digital age, OSINT is increasingly vital for identifying radicalization indicators, tracking extremist propaganda, understanding public sentiment, and gathering background information on individuals and groups.

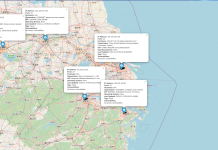

- IMINT (Imagery Intelligence): This is intelligence derived from the analysis of images and video captured by various platforms, including satellites, aircraft, drones, and handheld cameras. IMINT provides crucial visual evidence for monitoring locations (like suspected training camps), tracking physical movements, assessing damage after strikes, and identifying individuals or equipment.

- GEOINT (Geospatial Intelligence): GEOINT integrates imagery (IMINT) with geospatial information (mapping, terrain data, geographic features) and other intelligence sources to provide analysis in a geographic context. It allows analysts and operators to visualize the operational environment, understand spatial relationships, plan routes, identify potential targets or safe havens, and track movements over terrain. The US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) is a key provider of GEOINT.

The table below summarizes these key intelligence disciplines:

| Discipline | Description | Key Contribution to CT | Example Agencies (UK/US) |

| HUMINT | Intelligence from human sources (espionage, debriefings, interviews) | Insights into intentions, plans, group dynamics, information not technically accessible | MI6 (SIS), MI5 / CIA, FBI, DIA |

| SIGINT | Interception/analysis of electronic signals (communications, electronic emissions) | Tracking communications & networks, movements, technical capabilities | GCHQ / NSA |

| OSINT | Collection/analysis of publicly available information (media, internet, social media) | Identifying radicalization, propaganda, background information, public sentiment | All agencies utilize OSINT |

| IMINT | Analysis of images/video from satellites, aircraft, drones, etc. | Visual evidence, monitoring locations, tracking physical movements, damage assessment | GCHQ, MOD / NGA, NRO, CIA, Military Services |

| GEOINT | Integration/analysis of imagery & geospatial data (maps, terrain) | Visualizing operational environment, spatial analysis, planning operations, tracking | MOD, GCHQ / NGA, NRO, Military Services |

C. Intelligence Contributions to Counterterrorism

These diverse intelligence disciplines contribute to counterterrorism efforts in several critical ways:

- Identifying Threats: Intelligence is essential for detecting potential terrorist plots, identifying individuals or groups undergoing radicalization, recognizing emerging threats and capabilities, and understanding adversary intentions. This includes processing and analyzing suspicious activity reports (SARs) from law enforcement and the public.

- Tracking Terrorists: Intelligence enables the monitoring of known or suspected terrorists’ movements, communications, financial transactions, and support networks. This is vital for understanding their operational cycles and identifying opportunities for disruption.

- Disrupting Plots: The ultimate goal of much counterterrorism intelligence is to provide timely and specific, actionable intelligence that allows law enforcement or military forces to intervene and prevent an attack before it occurs. This includes issuing warnings to potential targets or the public when a credible threat is identified.

- Supporting Operations: Intelligence provides the necessary information to plan and execute counterterrorism operations, whether they be law enforcement actions like arrests and searches, or military actions such as raids or targeted strikes.

- Informing Policy and Strategy: Intelligence analysis provides policymakers with strategic assessments of the threat landscape, the capabilities and intentions of terrorist groups, the effectiveness of current strategies, and potential future developments. This informs national security policy, resource allocation, and the overall direction of counterterrorism efforts.

Success in counterterrorism intelligence rarely stems from a single source. Instead, it relies on the effective fusion and analysis of information gathered from multiple disciplines – the multi-INT approach. For example, OSINT might flag concerning online rhetoric. SIGINT could then intercept related communications indicating planning or coordination. HUMINT might provide crucial details about the plotters’ identities or specific plans from an inside source. GEOINT and IMINT could then be used to locate the plotters or monitor a potential target location. Combining these disparate pieces of information transforms raw data into actionable intelligence capable of preventing an attack. However, this fusion process presents significant challenges. Agencies must collect, process, and analyze enormous volumes of data from diverse sources, often under time pressure. They must do so accurately, while rigorously protecting sensitive sources and methods and adhering to strict legal and ethical frameworks governing surveillance and data privacy. Effective information sharing – both domestically between different agencies (intelligence, law enforcement, homeland security) and internationally with allies – is paramount but often hindered by bureaucratic, technical, or legal obstacles. Overcoming these challenges requires continuous investment in advanced analytical tools (including artificial intelligence ), robust and secure information-sharing platforms (such as fusion centers ), and highly skilled analysts capable of synthesizing information across multiple intelligence disciplines.

V. Building a Resilient Defense: Components of Counterterrorism Strategy

Effective counterterrorism requires more than just good intelligence; it demands a comprehensive strategy integrating various tools and approaches across government and society. National strategies often encompass the following key components:

A. Integrating Efforts

- Whole-of-Government Approach: Recognizing that terrorism touches multiple domains, strategies emphasize coordinating all instruments of national power. This includes intelligence agencies, law enforcement (federal, state, local), military forces, diplomatic channels, economic levers (sanctions, aid), border security, and information/communication efforts.

- Intelligence Fusion: As discussed previously, integrating intelligence from all sources and agencies is fundamental to understanding the threat and enabling action.

- Law Enforcement Actions: Domestic law enforcement agencies play a critical role in investigating potential threats, disrupting plots, making arrests, gathering evidence, and prosecuting terrorists through the legal system. Agencies like the FBI in the US and the National Crime Agency (NCA) and Counter Terrorism Policing in the UK are central to this effort.

- Military Intervention: Military force may be used, particularly against terrorist groups operating overseas that pose a direct threat, to degrade their capabilities, destroy infrastructure, capture or kill leaders, and deny safe havens.

B. Securing Borders and Finances

- Border Security: Preventing the entry and transit of known or suspected terrorists is a key defensive layer. This involves enhanced screening procedures for travelers, maintaining and sharing terrorist watchlists (like the US Terrorist Screening Center database ), using biometric data, improving physical border security, and international cooperation on travel security.

- Financial Countermeasures: Disrupting terrorist financing is crucial for hindering operations. This involves identifying and freezing terrorist assets, imposing sanctions on individuals and groups, tracking and interdicting illicit financial flows (which often intersect with organized crime, such as narcotics trafficking ), and working internationally to strengthen global Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) standards and capabilities.

C. Countering Narratives and Engaging Communities

- Counter-Propaganda/Messaging: Actively challenging and undermining the extremist ideologies and narratives used by terrorists to justify violence and recruit followers is essential. This includes efforts to delegitimize terrorist groups and their methods and counter their online presence.

- Community Engagement: Building trust and partnerships with communities is vital for prevention. This involves working with local leaders, civil society organizations, and faith groups to build resilience against radicalization, identify individuals who may be vulnerable, provide support pathways (like the UK’s Prevent/Channel programs ), and encourage reporting of concerns. Public diplomacy efforts can also play a role in shaping perceptions internationally.

- Addressing Disinformation: Modern strategies must also account for the threat of disinformation, which can be used by adversaries to amplify extremist narratives, sow social division, incite violence, or undermine trust in counterterrorism efforts. Countering such campaigns is becoming an integral part of protecting the information environment.

D. International Cooperation

Terrorism is inherently a transnational problem, making international cooperation indispensable. Key elements include:

- Intelligence Sharing: Exchanging threat information and analysis with allied nations and partner services (e.g., through arrangements like the Five Eyes intelligence alliance ) is critical for tracking global threats.

- Joint Operations: Collaborating on investigations, disruptions, and military operations against terrorist networks operating across borders.

- Capacity Building: Providing training, equipment, and technical assistance to partner nations to enhance their own counterterrorism capabilities (law enforcement, border security, judicial systems, financial intelligence units).

- Diplomatic Engagement: Building political will, coordinating policies, and working through international organizations like the United Nations and regional bodies like NATO to foster a united front against terrorism.

E. Addressing Socio-Economic or Political Grievances (Root Causes)

Many strategies recognize the need to address the “conditions conducive to the spread of terrorism”. This involves longer-term efforts to diminish factors that terrorist groups exploit, such as political exclusion, ethnic or religious discrimination, lack of rule of law, human rights violations, socio-economic marginalization, and unresolved conflicts. This component often links closely with development aid, governance support, and conflict resolution initiatives, aligning with the ‘Prevent’ aspect of counterterrorism.

F. Cybersecurity Integration

In the 21st century, cybersecurity is inextricably linked with counterterrorism. Terrorists exploit cyberspace for communication, recruitment, propaganda, fundraising, and planning. Furthermore, critical national infrastructure, essential services, and government systems are increasingly vulnerable to cyberattacks, which could be perpetrated by terrorist groups or state actors seeking to cause mass disruption. The potential impact was starkly illustrated by the ransomware attack on Synnovis, which severely disrupted NHS pathology services in London , and the activities of state-sponsored groups like Volt Typhoon, which pre-positioned on US critical infrastructure networks potentially for future disruption.

Therefore, comprehensive counterterrorism strategies must integrate robust cybersecurity measures. This includes:

- Protecting CNI from cyber threats using frameworks like the NIST Cybersecurity Framework or the NCSC Cyber Assessment Framework (CAF).

- Utilizing cyber intelligence tools and techniques for tracking and disruption.

- Countering online radicalization, recruitment, and propaganda.

- Coordinating efforts through dedicated cybersecurity agencies like CISA in the US and the NCSC in the UK.

The multifaceted nature of modern counterterrorism underscores the need for a multi-layered and adaptive strategic approach. Relying solely on ‘hard’ counterterrorism measures like military action or arrests may temporarily degrade a group’s capability but often fails to address the underlying ideology or grievances that fuel the movement, potentially leading to its resurgence or adaptation. Conversely, focusing only on ‘soft’ measures like prevention programmes may not be sufficient to stop imminent attacks. Financial tracking can disrupt operations but doesn’t eliminate intent. Border security is vital but can be circumvented, especially by homegrown extremists. International cooperation is essential but faces challenges. Cybersecurity adds yet another layer of complexity. Consequently, an effective strategy must weave together all these components – hard and soft power, domestic and international efforts, physical and cyber defenses, proactive prevention and reactive response. Moreover, given the dynamic threat landscape – the rise of lone actors, the speed of online radicalization, the exploitation of new technologies, and the shifting geopolitical environment – strategies must be flexible, continuously assessed, and adapted over time. There is no single solution or ‘silver bullet’ to the challenge of terrorism.

VI. Conclusion: Navigating the Complexities of Modern Counterterrorism

The fight against terrorism in the 21st century is a complex, dynamic, and enduring challenge. The threat itself continues to evolve, shifting from centrally controlled, hierarchical organizations towards more diffuse networks, ideologically motivated lone actors, and online communities that facilitate radicalization and planning across borders. Technology acts as both an enabler for terrorists – facilitating communication, propaganda, recruitment, and potentially new attack vectors including cyberattacks – and a critical tool for counterterrorism efforts through intelligence gathering and analysis. Persistent groups like ISIS and Al-Qaeda, despite setbacks, demonstrate resilience, adapting their tactics and exploiting instability in various regions.

In response, effective counterterrorism strategies must be comprehensive, integrated, and adaptive. They require a ‘whole-of-government’ approach, coordinating military, law enforcement, intelligence, diplomatic, financial, and informational tools. Central to this is the fusion of multi-source intelligence to provide a nuanced understanding of the threat and enable proactive disruption. Robust partnerships, both domestically between agencies and levels of government, and internationally with allies and partner nations, are non-negotiable for tackling a transnational threat.

Ultimately, countering terrorism is not solely about preventing the next attack; it is also about building societal resilience, addressing underlying grievances where possible, countering poisonous ideologies, and upholding the democratic values and rule of law that terrorists seek to destroy. This demands sustained political will, significant resources, continuous learning and adaptation, and a commitment to operating within legal and ethical boundaries.